My third book ‘The House on Silat Road’ was finally released in December last year. Soon after that, I was caught up in an exhilarating but frantic whirlwind of events at literary festivals, workshops and author talks at schools and museums—which also accounts for why I had not had the chance to post for a while.

My third book ‘The House on Silat Road’ was finally released in December last year. Soon after that, I was caught up in an exhilarating but frantic whirlwind of events at literary festivals, workshops and author talks at schools and museums—which also accounts for why I had not had the chance to post for a while.

The House on Silat Road, which my mum and I took almost a year to pen, was the most intense piece of writing I have ever done. Set in Singapore during the harrowing Japanese Occupation in WWII, the book is based on my mother’s childhood memories as she and her family of 13 endured the war from 1941-1945. She wrote the first few drafts all laden with information, and forming the skeleton of the story. Then I did many rounds of editing and rewriting, which turned her very vividly recalled accounts into a children’s chapter book. It was her story, and her 9-year-old self was the protagonist Sing. My job was to bring out the mental images, the sights, sounds and sensations, characters, and dialogue—in other words to flesh out the stories and bring the characters to life.

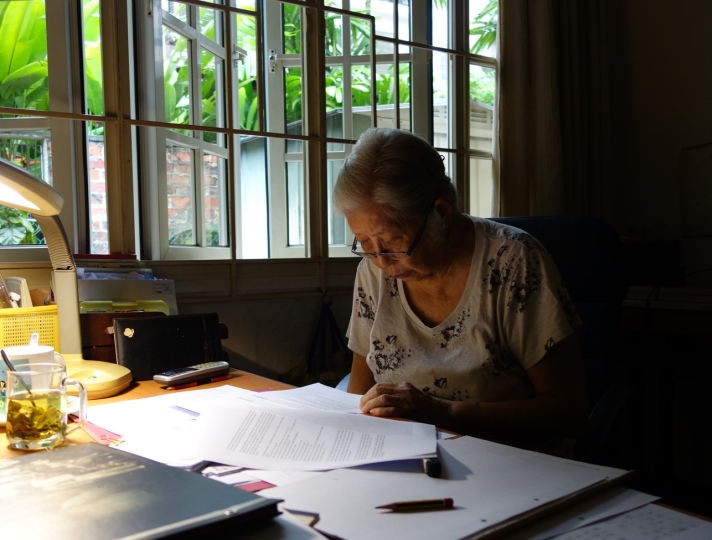

We spent many many afternoons together poring over details of her memories. (For an 86 year old, her memory is amazingly photographic.) Not surprisingly, some afternoons with my mom were made of enjoyable conversations and touching reminiscences. Then there were other days when our sessions descended into testy exchanges and heated disagreements about how the book was to be written. But that was all part and parcel of working on a joint project that we both wanted to succeed. Then I would go back and do my research—from newspaper clippings, old maps, and archival images to oral histories and the memories of her older siblings—to ensure her childhood memories matched up with historical facts and social setting of the time. When I was ready to put fingers to keyboard, I would retreat to my study at home and play out the scenes in my mind’s eye, to capture the details and try to see, hear, feel, respond to the different scenarios from the viewpoint of a 9 year old—that was how old she was when the Japanese swarmed into Singapore that many decades ago and turned their lives upside down. To capture it on a page and flesh out her initial drafts, I needed to relive her experiences as best and as vividly as I could, and that was how it became so intense.

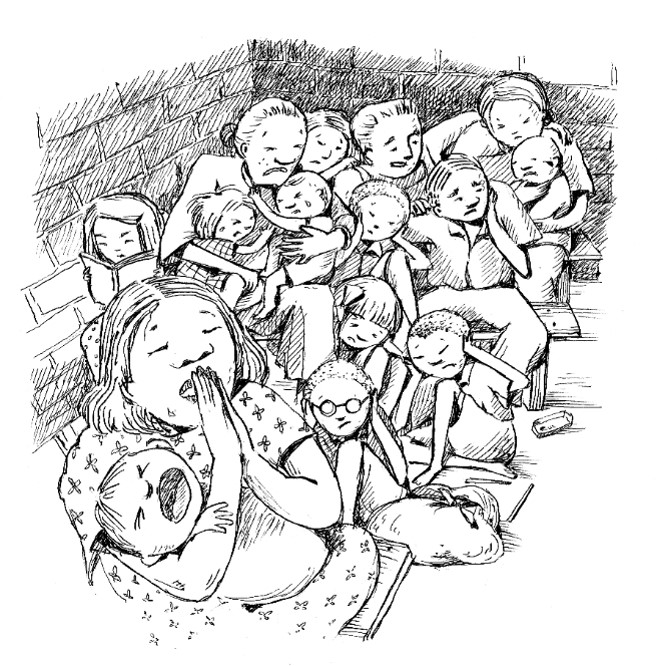

Every afternoon, armed with my information, research and her drafts, I retreated mentally to the war years of Singapore—back to her home, her family and her, as best as I could. And like a ghost from the future, I tried to witness the family in the scenes I needed to describe and let it unfold—to see and feel what it was like when the first air raid happened, when the Japanese were bombing Singapore, for instance. I needed to capture details in my mind’s eye. I needed to picture how the bedroom looked as the children were woken by the siren for the first time. What was the route they took from the bedroom to the bomb shelter when the bombs fell? How did the air raid shelter my grandfather built look like, what did the walls and benches look like, how cramped and damp was it, and what did it feel like when the bombs fell? How did it sound and feel like on detonation? How did people think and feel? What did they say to each other as the bombs fell? What was in my mother’s line of sight as she huddled with her family in the darkness? Did she have her hands over her ears? Was she crying? What did a 9-year-old think and do and feel and respond as bombs fell around her, intended to kill as many as possible, including her young self? How does one feel hearing bombs falling around them for the very first time?

If the scene I captured and edited was not to my satisfaction, I would return mentally to the bombing scene again and again. I spent over a month writing and rewriting that chapter until I was satisfied—but that meant mentally going back to the bombing on the night of 8 December 1941 almost every afternoon in my quiet peaceful study. Every evening when I emerged, I felt physically drained.

Every so often as I built the scene layer by layer, I would realise I needed more and more details, and believable ones at that. For it was the details that were crucial in making every incident believable, vivid and authentic. So I grasped at whatever my mother told me about her experience, wrote notes and queried her again and again. More information gave me greater room to build and recreate the scenario as it unfolded. I needed to make it so vivid (yet without being contrived) that it would suck our young readers into that moment with the protagonist – my mother at 9 years old. Just like I was sucked in.

I guess they were memories she did not want to revisit, but in reluctant doses, she would tell me nuggets of horrifying information, like how you could not hear aerial bombs approaching while inside the bomb shelter. You would only hear them explode, and that’s how you’d know you had survived that bomb. So she and her family—huddling in the hot and humid air raid shelter that was once grandfather’s car garage—would listen out for the explosions so they knew they were still alive until the next bomb came almost immediately. When she could not find the words, Mum also reproduced the spitting-hissing sound of approaching artillery fire of WWII, and explained in detail how the sound of artillery and bombs differed, and how, if you heard the spitting sound of artillery fire coming from behind you, “you’d better run”. She also told me how slow WWII warplanes travelled, so as the neighbourhood’s appointed lookout, her brother would watch the approaching planes from their rooftop garden, wait until it was ‘near enough’ before he sounded the alarm for the neighbours to run and take shelter, all in good time.

What hit me really hard was realising all these details were learnt experientially by a 9 year old girl, and she would be little different from kids today. She would have had little understanding of the politics of the time, but was caught up in a frightening adult’s war. To have to deal with the idea that death could happen anytime at such a young age, was horrifying.

There were so many other events recalled in the book: how my grandfather had to submit himself to the terrifying Sook Ching screening where over 50,000 Chinese men in Singapore were arbitrarily massacred in a period of two and a half weeks; how Japanese soldiers stormed their house with ropes and bayonet-tipped rifles looking for my grandfather, to seeing the return of the allies towards the end of the war, when American warplanes bombed our harbours and inadvertently civilian homes to pave the way for taking back Singapore from the Japanese, and when their home was bombed by incendiaries. I had to relive all these scenarios with the same level of intimacy of her memories, and again they were all mentally and emotionally draining. To think that she had to endure that in real life all that time ago was beyond me.

But in all her young innocence, she also found simple pleasures in a world a child could not have understood. Planting vegetables in their garden, raising chickens for eggs was fun. But the underlying urgency to do that was lost on her—that it was necessary for basic survival.

On a happier note, we also captured her joy in seeing leaflets dropped by allied planes over Singapore to announce the Japanese defeat—it must have been amazing spectacle with good news literally fluttering down from the sky as far as eye could see. I could imagine how ecstatic she would have felt, knowing it marked the end of their suffering. And then her eye-witness account of the allied fleet sailing into Singapore’s harbour in September 1945 to receive the formal Japanese surrender in Singapore.

Many of these accounts are not in history books and it was such a privilege to relive it (as best as I could) through my mother’s very detailed memories. It was like walking back in time together with her, back to her home, her family and her experiences. It was almost like getting to know my mother as a child. It was a different perspective which I cherish.

And here she is now, at 86 years old, writing this story with me. Knowing so intimately what she went through made me love and respect her more, for she emerged with an incredible stoicism, resilience and strength of character. It made me appreciate and understand her better. After all that, she became one of the first women in Singapore to graduate from university with a science degree and go on to earn a master’s degree in chemistry. That made her a most atypical woman of her generation. Now, in her 80s, she has embarked on a new career as a children’s author. She pretends to complain that I work her too hard, but I really think she enjoys the attention—especially when young readers swarm around her to sign their copies of her book at school talks or at bookstore signings, ask her more questions about her childhood or just reach out to hold her hand. (Perhaps they just want to feel that she is real. I would post those pictures if not for the privacy of those children.) And she still is one of the most unique, unconventional women of her generation now. How proud I am of her.

Congratulations on the book! What a fantastic opportunity being able to work with your mother to document a moment in history usually told from military and governmental points of views. Did you find that you learned something about the methods of your own upbringing or about yourself from this project?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I didn’t learn much about myself, but certainly learnt a lot about my mum and her family. And things about the war that one does not find in history books — like the mindset of people living under siege, their concerns and considerations, like where to get food and how to survive, right down to the smallest details like planning one’s walking route to avoid encountering the Japanese. It was fascinating. Plus lots of other historic details about the war that seem to have been forgotten by our historic narrative. I hope to post more of those discoveries soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is wonderful. How has your other book been doing, “The House on Palmer Road?”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, hello. 🙂 Thank you for remembering my other book. It has been doing well, and into the 2nd print run. It has not won any awards (yet!) but it’s on our national library’s recommended reading list for kids, and have been picked up by some schools as a ‘reader’ for 8 year olds. So we’re so pleased — it’s more than we imagined when we set out with the project. 🙂 How is your book writing journey?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is great news! Wonderful to hear you are in the schools. My book journey is coming along. Trying to finalizing two different books to send out to Agents. One day soon, I hope to have great news for you. Good luck with the book you are working on now.

LikeLike

An amazing journey you and your mother agreed to partake together and one you’ll cherish forever. Congratulations on the book!!

LikeLike