First of all, let me state outright that this post may not go down well for some as it presents some ugly truths. On the anniversary of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many call for an end to nuclear weapons, while the Japanese who suffered the mushroom cloud mark the anniversary with tears and respect. But every August, I remember with gratitude the brave Americans who flew the bombers over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, risking their lives, to save the lives of millions of others from Japan’s brutal and senseless war across Asia. It was Japan’s own doing 76 years ago that drove the world the brink, and left the world with little choice but to drop not one but two atomic bombs to make them stop. As far as I am concerned, the bombs were fully justified. I may not have lived through the war, but my country and fellowmen were victims, and we must never forget that part of our history.

I live in an area in Singapore that was nicknamed The Valley of Death in the 1960s. But you would never ever guess if you toured the very comfortable residential districts of Siglap, Bedok and Chai Chee these days, with their many flats, malls, parks and schools. This area is my hunting ground where I do my grocery shopping and run errands. Up in Changi, there is the bustling, glittering Changi airport, and by the long stretch of beaches, people picnic, jog, bike and lots of marathons are held there on weekends.

But not that long ago in the 1960s, many volunteers and undertakers had the grim task of locating and exhuming no less than 40 mass graves in this area. For this was the killing fields of Singapore during the Japanese Occupation in 1942-1945.

One of the mass graves held two thousand bodies. It was located in what was a rubber plantation during the war. Seventy-six years ago, over 250 civilian men were executed there on one occasion. Countless more followed. On that site now stands Temasek Junior College. The teenagers who attend school there every day are oblivious of the grim history of their campus.

Indeed, most Singaporeans are not aware that there was once mass graves in Singapore. From the treadmill at my gym at Amber Road, the view outside overlooks a shaded private carpark that lies beyond the swimming pool. Few people know that the carpark was once the beach line, where 76 years ago, two lorry loads of frightened men were made to dig their own graves, then gunned down. It is now surrounded by spanking new condominiums.

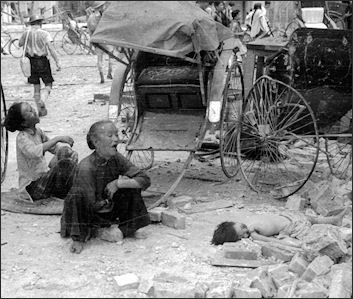

All these mass graves contained the victims of the infamous Sook Ching that took place from 21 February to 4 March 1942. It was WWII and Singapore had fallen to the Japanese earlier in February. The Japanese wanted to weed out people in the local populace who held anti-Japanese sentiments—but who wouldn’t object to people who invaded their country and bombed it for three months prior?—and the Sook Ching screening was designed to do just that.

The Japanese focused primarily on the Chinese community, but all the other ethnic communities in Singapore were affected too. In the Sook Ching, all Chinese men between 18 and 50 had to report to ‘inspection centres’. They had little choice. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Not surprisingly, thousands did not return. My grandfather had to go, and he witnessed how men were singled out by the Japanese like a game of Russian roulette – in one centre, all who wore spectacles were taken away; in other centre, every third man was, and yet another, all those who could speak English were taken away. It is well known in Singapore’s collective memory and archives that they were brought to the beaches and various other rural areas mostly in the east, forced to dig their own graves and shot. And that’s where they lay until they were found and exhumed in the 1960s. The remains are now interred in over 600 urns at the civilian war memorial in Stamford Road in Singapore.

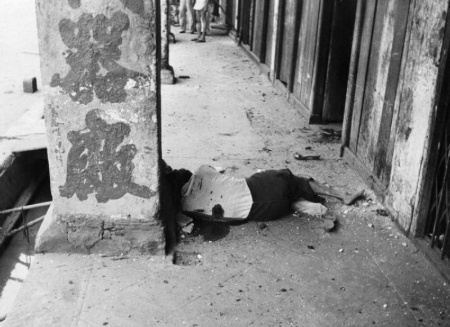

Even though the Japanese Occupation in Singapore has long been over, many families here remain affected by it—there are grandfathers, fathers and brothers who people never knew, little brothers who had been taken away on a whim by Japanese soldiers, babies who were tossed in the air and used for bayonet practice, POWs who were also used as practice targets, cruel human experiments from amputations without anaesthesia to biological testings in Changi. Their list of atrocities is long. All these are still in the living memories of the older folk – not rumours but traumatic memories — and recorded in our national archives.

My mother who lived through the war told me all this. She was only nine then. She survived the fearsome bombings before the Fall of Singapore and to this day remembers how aerial bombs and artillery sound. She still cannot bear to hear simulations of the air raid alarm sometimes played out in museums, nor walk through museum galleries that record the war years. It reminds her of too many awful things she saw during the Japanese Occupation – like the decapitated heads of people murdered by the Japanese army displayed on stakes in front of the Cathay Building in Orchard Road for the populace to see and be warned.

My grandfather had gone to the Sook Ching inspection and was lucky to survive. He was helped by a stranger, a local interpreter for the Japanese, who convinced them that he was not the resistance fighter that they were looking for – just that his name sounded a little similar. My grandfather did not know the interpreter and was so grateful to him for saving his life. My grandfather lived to an old age after that, but thousands did not.

The number of men killed just as a result of the two-week Sook Ching screening was estimated to range from 50,000 to 70,000. Most of them were Chinese. Why the Chinese? The Japanese had invaded China in 1931, and the two countries had been at war since then. Amongst the awfulness of war, the Rape of Nanking in 1937 was still fresh in the minds of the people, where over 300,000 people were killed, some in the most barbaric of ways. The Chinese in pre-war colonial Singapore still saw China as their motherland, and did all they could to support China’s war efforts. They sent lots of money back to China, and the Japanese naturally did not like that.

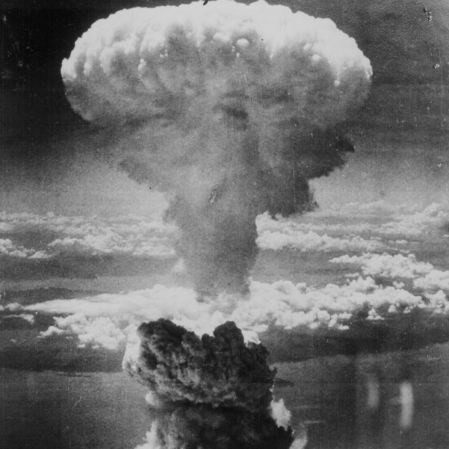

By the end of the war, the death toll across the world as a result of Japanese aggression ran into the tens of millions. So intent were the Japanese on perpetuating the war that it took not one, but two atomic bombs for them to stop.

On August 6, 1945, the American bomber Enola Gay dropped a five-ton bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. A blast equivalent to the power of 15,000 tons of TNT reduced four square miles of the city to ruins and immediately killed 80,000 people. Tens of thousands more died in the following weeks from wounds and radiation poisoning. Three days later, another bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, killing nearly 40,000 more people.

I grew up listening to stories about the war from my parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles who survived the horrific Japanese Occupation in Singapore. Many years later as an adult, I visited the Hiroshima peace memorial. There was a plaque in front of the famous bombed dome which said something like “on such and such a day, an atomic bomb was dropped on humanity”. I was very angry when I read it. I felt offended on behalf of all those killed by the Japanese during the war. The atomic bombs were dropped on Japan by humanity to save millions of others who would otherwise have been killed if Japan was allowed to continue its aggression. Because at that time, Japan had lost its humanity. The atomic bomb was most certainly not “dropped on humanity”.

While the Hiroshima Peace Park commemorates the suffering of the Japanese in 1945, it should also stand as a stark reminder to their younger generations and indeed the rest of the world of the time when Japan waged war on humanity so cruelly that indeed humanity was driven to detonate such a terrible weapon on them to stop their cruelty, and indeed to preserve the rest of humanity. Not one, but two before the Japanese stopped.

Many argue that the atomic bomb was cruel; that people suffered for months and years later. But guess what? How about the murder of an estimated ten million at the hands of the Japanese army, from innocent civilians to POWs? Consider the Rape of Nanking, the Death Railway, the POWs and innocents who suffered, and those who fought at all the other fronts in the Asian theatre. Ask anyone who had suffered through the war in Asia, tortured in interrogation centres, and saw family members killed on a whim, if they were concerned that the atomic bombs were ‘too cruel’. If not for the bomb, my family and millions of others across Asia would not be around. If not for the bomb, we may not have peace today without the loss of millions more innocent lives, from civilians to Allied soldiers across the Pacific.There is no need for America to apologise for the bombs. It would be a slap in the face for all those, civilians and soldiers, who died fighting the good fight in Asia. No, I thank America for doing so and bringing the war to a quick end and saving so many others. The death toll from the bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki ran into thousands; sad as it was, it pales in comparison to the millions they killed.

What disappoints me is that despite official apologies from the Japanese government, the war and Japan’s actions remain nothing more than a footnote in Japanese school text books, and continues to be presented–if at all–in a way that exonerates themselves. War criminals are still honoured at their temples and they still weep for their own suffering. It is no wonder that distrust still runs deep in the region, for the apology rings painfully hollow as Japan continues to play the victim of the atomic bomb every August, with neither mention nor thought about their inhumanity to the rest of the world over 76 years ago.

Lest We Forget.

(Photos from various archives.)

My husband and I have had some chats about some of this. I’m sure that he would agree with much if not all that you’ve written here. And as you know, he’s Japanese. Having lived most of his life outside of Japan he thinks differently. May the souls of all wars ravaged on this planet rest in peace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Mrs N. Thank you for taking the time to drop a note. It means a lot to me. My view is not to hold on to the sins of the past, but it is also important to confront it, remember it, and still have the ability to move ahead despite it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I understand. Completely.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You are a great cook, a great writer and your historical perspective is absolutely 100% correct. The Japanese murdered something like 10 million Chinese alone, it worked out to something like 10-15,000 people every single week for more than ten years. Lest we forget.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for dropping by my blog again, and for your kind words. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a tough one. My father was Japanese and grew up in the destruction of WWII, and my mother is American. I am an American, but I look very “Japanese”. My great-uncle was an American sailor who was at Okinawa during the “Rain of Steel”, on the “LST-447”. I was apparently the only person he ever talked to about his experience there. My university background in the US was Physics, and I chose to pursue a graduate route that resulted in something that I can’t even discuss. (This is the first time I’ve shared this directly here.)

I’m no apologist for Japanese actions in WWII… or for that matter, for any of Japan’s preceding military occupations. Japan’s Imperial ambitions amounted to a collective act of social psychopathology. The extraordinary brutality was well-documented. There were cases when even some Japanese-allied German observers protested the senseless and indiscriminate massacres of civilians by Japanese forces. I don’t for a second doubt anything that your post mentions, and I also don’t think it should be whitewashed away.

Not all of Japanese society, however, was supportive of Japan’s Imperial aspirations. The massive casualties of the Russo–Japanese War, or “Nichirosensō” in 1904/5, which foreshadowed the mechanized destruction of WWI, soured many Japanese on the idea of military expansionism. Some of my own articles here document the kinds of domestic protests that emerged from segments of the civilian population, and at no small risk in a society where lèse-majesté laws could land one imprisoned… or worse. Even many soldiers felt that their efforts were a waste. Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney’s collections of letters from Kamikaze are very enlightening.

Growing up in such an environment, I’ve come to see warfare as a case where individual humans more-or-less sacrifice their personal identities to those of their societies. And societies don’t feel compassion, love or hate, or joy or suffering. They simply compete in an ultimately utilitarian manner. Individuals, however, do suffer. It’s the reason that I believe we must never be willing to sacrifice our own sense of compassion for others, and individuals must always be willing to accept personal responsibility for their own choices and actions, and especially in war.

I say this objectively, and the ethical ramification can be debated regardless. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were primarily experiments as well as demonstrations for the Soviets, and had debatable strategic value in the war with Japan. The Hiroshima bomb was the very first ever detonation of a simple uranium-fueled device, and actually proved quite inefficient. The Nagasaki bomb was of the type first tested in White Sands, New Mexico on July 16, 1945. It used Plutonium, since uranium of the type needed for a bomb was so difficult to refine at the time. This bomb was first built with the intention of dropping it on a German city, also largely as a warning to the Soviets. However, the war in Europe was over by the time it was completed, and the Soviets were poised to invade the island of Hokkaido in northern Japan.

Regardless, by this point in the war in Japan, the effects of the atomic bombs paled in comparison to the devastation left in the wake of the relentless fire-bombings of sixty-seven major Japanese cities. The victors were able to write the histories and to come up with their own numbers and justifications; but one-hundred thousand civilians lived in a single square mile of just Tokyo’s Shitamachi District. The images are no less horrific than those of mass graves or bayoneted babies. My late aunt’s stories of her childhood experiences included fleeing into the Nakagawa (river in Tokyo), and sheltering among hundreds of charred, floating bodies of the dead and dying. I don’t know if it was necessary; maybe it was. But being burned alive is not something I would wish on anyone. And at some point in my life, I decided that it was not something I could cause to happen to another human being.

I’ll leave with this. I followed your “like” here, and I appreciate it. The woman whom I mentioned in my comment was the Filipino mother of an old friend. She grew up on a small island near Leyte. She told my American husband that during the war, the Japanese told the people of her village that if they returned from hiding in the jungle, they would be given ID’s and allowed to live in peace as long as they didn’t cause any problems. About half of the village returned. They were all killed. She didn’t want to tell me the story because she was afraid that it would somehow hurt our friendship. Regardless, she was somehow able to move past her own terrible history and see me as a close friend. I felt genuine kindness from her, and cared for her deeply. So if there’s a moral or a message to all of this, maybe it’s just that we all have to somehow learn to move past what societies and “civilizations” may demand of our collective identities, and simply care about each other as people.

LikeLike

It is quite a coincidence that I am replying you on the anniversary of the Japanese surrender in WWII. Thank you for reading and for sharing your thoughts. I appreciate the balanced view that you present and I appreciate your sharing personal vignettes. There are those who question if the bomb was necessary. In my view, it was, though I am not unaware of the suffering it also brought to the Japanese. Then again, I am not here to debate this topic. There will always be different camps in this argument, and so be it. I do agree with you though that ultimately it is necessary to move on despite the past and hopefully be better people. In order to do so, the war years is not something that we should forget.

LikeLiked by 1 person